Menu

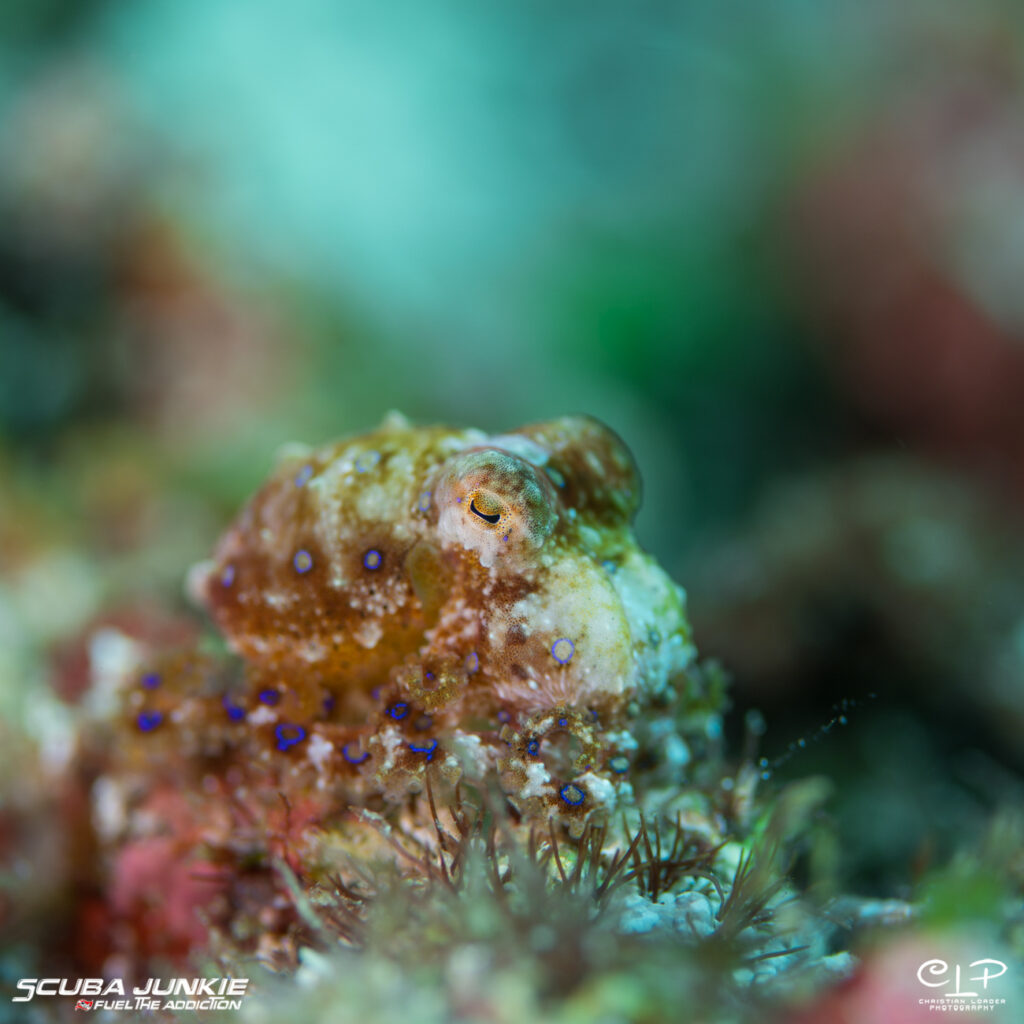

The Blue Ring Octopus is on almost every diver’s bucket list and if it isn’t on yours it should be!!

This small octopus is without doubt a stunning creature to see and many divers choose to go to special places just to see them. So let’s dive in and learn a little more about these incredible animals!

Blue Ring Octopus are part of the genus; Hapalochlaena and actually refer to a group of species rather than a single one.

They are part of the Class Cephalopodea. The name Cephalopod comes from the Greek words ‘kephalos’ for head and ‘podos’ for foot. They that get their name because their limbs are attached to their head!

These small octopus get their name from the iridescent blue rings that cover their body. When they feel under threat these blue rings flash to ward off predators. These blue rings are an example of aposematism, where animals use bright colours to warn off other animals / predators, but unlike other animals that posess this method of defence the rings of the Blue Ring Octopus only light up & flash when they feel under threat. The remainder of the time they are still visible, but just barely. (If you can get close enough for a look!)

Blue Ring Octopus have been found in the Pacific and Indian Oceans and tend to inhabit rocky or algae areas so are most commonly found on dive sites that we would class as muck-diving or macro sites. Here in Komodo we tend to see Blue Rings on the dive sites of Karang Makassar (or Manta Point), Gindang & Waenilu, but we have also spotted them at Batu Bolong and Shark Point!

Blue Ring Octopus are small so it really does take a keen eye to spot them. They tend to be nocturnal in nature often coming out at night to hunt. They spend a lot of time tucked under algae, or hiding under crevices to avoid being seen by potential predators.

Did you know there is more than just one Blue Ring Octopus?! There is thought to be 10 different species of Blue Ring Octopus, but only 4 have been named.

The Greater Blue-Ringed Octopus (Hapalochlaena Lunulata)

This is the one we see here in Komodo. It is found, not only here in Indonesia but also, in the Philippines, Vanuatu, Solomon Islands and Papua New Guinea. It tends to prefer the shallows can is found up to about 20m deep.

The Southern Blue-Ringed Octopus (Hapalochlaena Maculosa)

This Blue Ring lives in water up to 50 m deep. They have only been seen along the Southern coast of Australia and Tasmania. This Blue Ring is much bigger than the Greater Blue-Ringed Octopus (even though the name would suggest otherwise) as it can be about 22cm long (including the legs). The Greater Blue-Ringed Octopus is about 12cm.

The Blue-Lined Octopus (Hapalochlaena Fasciata)

This one is a little different as it has iridescent lines alone it’s mantle (the back of the head that gives it the octopus shape), but it still has the classic blue rings on its limbs. This octopus is found in Eastern Australia and is about 15cm long.

Hapalochlaena Nierstraszi (No common name)

This species of Blue Ring has only ever been recorded twice. The first time in 1938 in the Andaman Islands and then a second time in 2013 in Southeast India. There is very little know about it.

As I have said this animal gets its name from the iridescent blue rings on its body. These beautifully vibrant rings are not just for show. They are a warning. If the warning is not heeded the Blue Ring Octopus can release tetrodotoxin (TTX) from its salivary glands. TTX is neurotoxic & blocks the transmission of nerve impulses. This stops muscles being able to contract and can have a deadly outcome for the victim. Paralysis will occur as the toxin takes affect and death is due to respiratory failure as the muscles fail to work. This can occur in just a few minutes of exposure.

Some studies state that TTX is 1000 times more toxic than cyanide. Blue Rings can inject this into their victims through a bite. There is no known antidote for TTX.

Thankfully incidents of humans being bitten by Blue Ring Octopus are very rare, with most of these little creatures choosing to move away and hide away from danger rather than aggressively attack!

Blue Ring Octopus feed on smaller animals such as small crabs and shrimp. They are masters of camouflage & ambush. They will hide until their prey is within reach and then the will ‘leap’ out and wrap around them with their limbs. They make a small hole in the shell and inject venom (different to what they use for predators) into the hole causing paralysis of the victim. This allows the octopus to suck out the tasty meal and leave the empy shell or exoskeleton behind.

Mating is quite a sad affair as it results in the death of both the male & the female. Blue Ring Octopus live for about 2 years and like with other octopus they usually reach sexual maturity before 1 year. One of the limbs of the male is specially adapted for mating. The male inserts this into the oviduct of the female to release the sperm. Once this is complete the male dies.

The female will then carry the sperm until she is ready to lay her eggs. When the female has laid her eggs she will guard them until they hatch. This usually takes about 50 days. Once the eggs hatch the female usually dies too as she does not hunt or eat during this time putting all of her energy into protecting her eggs.

Blue Ring Octopus are incredible creatures and a true sight to behold underwater! So many divers ask to see them on their trips and photographers love to catch them in their full iridescent glory!

Next time you are in Komodo be sure to keep your eyes peeled in the cracks and crevices to see if you can find yourself a beautiful Blue Ring Octopus!

Here is a special tip from one of our favourite Divemasters Indra!

“Untuk cari Blue Ring itu harus di karang yang mati. Di situ tempat yang paling seringkali mereka ada. Seperti di Manta Point dan yang paling sering mereka keluar itu untuk mating dan hunting itu jam 2 sampai sore”

“To find Blue Rings you need to look in the dead coral. This where they are most often found. Like at Manta Point. The most frequent time for them to come out for mating & hunting is from 2pm into the afternoon!”

All photos courtesy of Christian Loader

Komodo National Park is famous for our healthy population of reef mantas, the number of reef sharks and turtles and the stunning reef-scapes, but did you know that we also can see the elusive, and almost mythical – Dugong!!!

Over the years we have shared videos and photos of our various encounters and many of our guests ask us how and when is the best time to see these incredible mammals. We will get to that, but first lets learn a little more……..

What is a Dugong?

Dugongs are part of the animal order Sirenia. Their scientific name is the ‘Dugong Dugon.’ The Sirenian family is made up of 4 large aquatic mammals – 3 species of manatees and 1 Dugong. The family was first classified in 1776!! There was a 5th species (another Dugong species) that was originally the largest of this family.

The Stellar’s Sea Cow in the Bering Sea was formally identified in 1742, but it was completely wiped out by humans within just 30 years of being scientifically identified.

It is believed that the Sirenian order has been around for 40 million years. They are classified in the same groups as Tethytheres which means they are connected to Elephants! Can you see the resemblance?!

A Couple of Fun Facts

Dugongs are usually nomadic and solitary, but can be seen in small groups or ‘herds.’ The largest herd seen at one time estimated to be 450 individuals. They may be solitary but they are very good mothers and stay with the offspring for about the first 18 months of their live.

Reproduction

There is no obvious way to tell the sex of these animals. They take about 10 years to reach sexual maturity and gestation lasts 12 months. They are thought to give birth every 3-7 years and as mentioned will stay with their young for the first year and half of their little life!

When a Dugong gives birth the first thing the mother does is push her baby to the surface so it can take its first breath. The mum will do this a couple of times until the baby gets it’s bearings and can do this itself! New borns already way about 30kg and are about 1 meter long.

Swimming / Movement

These large mammals often appear docile and slow moving, but don’t be fooled as they can swim fast! They have been recorded swimming at speeds of 22km per hour when needed!! We, divers, will not be able to keep up!

When sleeping these gentle giants go into a trance like state and can look as if they are just ‘hanging’ in the water. Dugongs never fully ‘sleep’, but do actually go into a trance like state where the rest parts of their brain to rest. During this time they will be perfectly still, but as they are not fully asleep they can rouse quickly if any danger is close by.

Seagrass

Dugongs main source of food is seagrass which is commonly found in Indonesian costal waters. Seagrass makes up 0.2% of the world’s oceans. It is found in shallow areas with low turbidity. There are 60 known species of seagrass of which 24 of these are found in the Indo-Pacific region.

Seagrass is known to have an important role in carbon storage, accounting for 10% of the annual carbon sink capacity of the oceans.It has been estimated that a hectare of the most effective seagrass areas exceed more than 10 times the carbon sink capacity of the famous Amazonian forest.

Dugongs in Indonesia

General population numbers in Indonesian waters remain unclear. Estimates range from 1,000 – 10,000 individuals, but we don’t really know as there is little scientific data to note.

However Dugongs are protected by National Legislation in Indonesia and there has been a National Conservation Strategy specifically running for Dugongs since 2009. Dugongs are commonly sighted in

Nusa Tenggara Timur, Sumatra, Java, Kalimantan, Sulawesi, Bali, Baluku and Papua Barat.

The Dugong & Seagrass Conservation Project covers 8 countries and represents the first coordinated approach toward the conservation of Dugongs & Seagrass. It runs projects in Indonesia, Madagascar, Malaysia, Mozambique, Sri Lanka, Solomon Islands, Timor-Leste and Vanuatu.

Cultural Significance in Indonesia

The Indonesian word for ‘Dugong’ is ‘Duyong’ which actually translates to ‘mermaid’. These creatures are mythical in their history and mermaid stories from sailors are thought to have been inspired by Dugongs who were often seen in shallow waters and are able to turn upright in the water to put their heads out of the water. There are even tales of tribes covering sick Dugongs in cloths to cover their modesty when found in shallow water.

In Indonesia Dugongs are also revered and protected by many communities as they are thought to represent re-incarnated women, but for others their teeth, tusks, teats, and even their tears were considered to have magical properties so they were often used for healing or to produce religious artifacts.

Dugong Etiquette while Diving

We can see Dugongs pretty often in Komodo and although many will tell you, there is not really a ‘season’ for them, but what we do find is that when we spot 1-2 they will tend to hang around and be frequently sighted for a couple of weeks before ‘disappearing’ again! We see Dugongs at a couple of different dive sites here. Just recently they have been seen at The Cauldron (aka Shotgun), Polis Point and Tatawa Kecil. We also have a very special dive site here where we do see them a lot, but we prefer not to share the name so we can protect this area! We will take you if you visit though!!

Dugongs have very poor vision due to tiny ears, but they are acutely sensitive to sound with very narrow sound thresholds. This all just means they do not like sound!

The most important rule when looking for Dugongs is not to make any sound underwater – so we will always brief you that if we are searching it is very important not to use any tank bangers or clickers as there is a high probability this will scare them away!

It’s also important that there are no boat engines nearby as that will also spook them.

Dugongs are incredibly majestic animals that are on many divers’s bucket list! Here in Komodo we are lucky to be able to spot them on different dive sites and we would love you to come and see them with us!

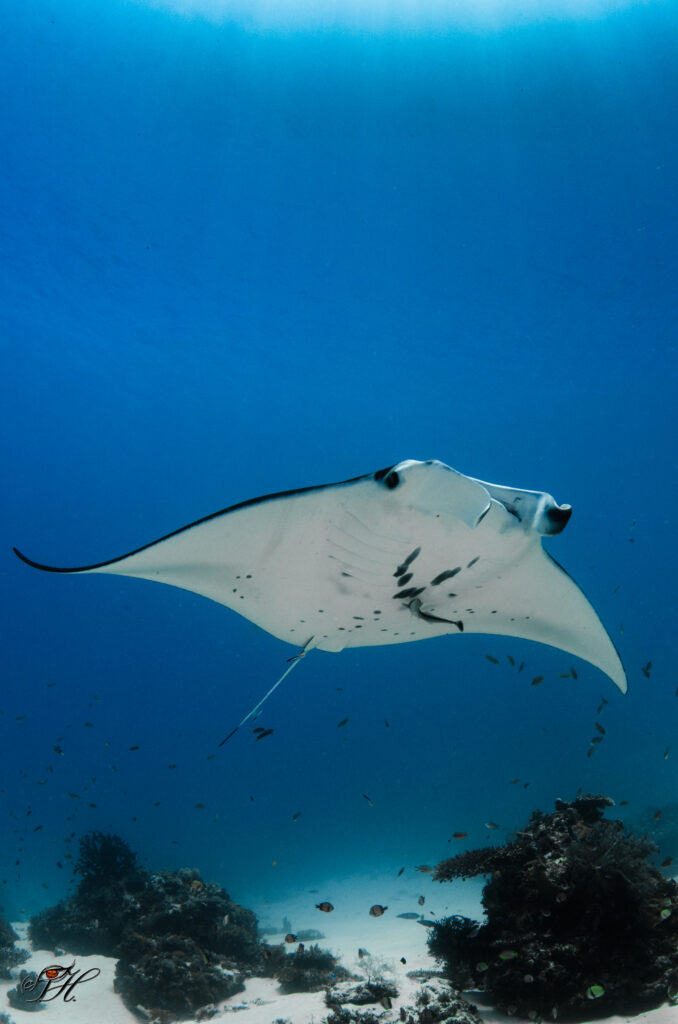

The Mantas of Komodo National Park are a popular reason to visit this incredible area! They love to hang out in the waters surrounding Komodo and our resident population continues to grow year on year!

Mantas are part of the Eslamobranch Family. This is the same family as sharks and skates and is due to their cartilaginous skeletons. Sharks have been around for over 500 million years while this younger relative has only been around for about 5 million years.

Mantas are actually formally called Mobulids and were officially renamed a couple of years ago, but for us they will always be Mantas!!

These graceful animals are smart too! They have the largest brain of all fish making them highly intelligent creatures. Studies have been conducted using mirrors in what is called a Mirror Self-Recognition Test (MSR). This is used to see if an animal is self aware. Cats & dogs for example don’t recognise their own reflection and act as if they are meeting another cat or dog! Other animals that have ‘passed’ the MSR tests are dolphins, elephants and primates. MSR is tricky underwater, but mantas have excellent vision compared to other fish.

When studied in front of a mirror mantas have been seen to spend more time in front of the mirrors than in other areas and they were observed to perform repetitive and unusual behaviours that is known as “contingency checking” in other words – checking themselves out! They do not respond to their reflection as if there is another buddy around. Like primates & elephants they are thought to be able to recognise themselves. Self-awareness / self recognition is a fundamental factor when determining intelligence in animals.

These flying giants live a life of perpetual motion – meaning they always keep moving. They must constantly keep swimming over the course of their lifetime. In fact, the only time they stop swimming (briefly) is during copulation (sexual activity). Mantas are very heavy with the biggest known specimen weighing 2 tonnes! So when they stops swimming they are negatively buoyant and will start to sink.

There are 2 types. (A potential third kind is currently being studied by scientists, but yet to be formally announced).

Here in Komodo we get the Manta Alfredi or Reef Manta. These are the smaller of the two, but can still grow very big with an average wingspan of 4 metres! Reef Mantas prefer shallow reef waters and can be easily identified by the belly spots between their gill slits.

The second kind is the Manta Birostris or Oceanic! These are HUGE with an average wingspan of 8 metres and are more commonly found in deeper waters in places such as the Galapagos and Socorro Islands, but they are also commonly seen in Raja Ampat. Oceanics can be identified by their huge size, but also by their belly spots which are found outside of their gill slits.

Here in Komodo we have a resident population of just over 1200 Alfredi individuals. These individuals have all been uniquely identified by their belly spots.

Did you know every manta has unique spot patterns on their bellies, which is just like the human fingerprint. These patterns are what is used to identify and track individuals. This is why citizen science and photos / videos are so so important. Scientists use this information to identify, track and monitor individuals and populations.

Manta Matcher is a fantastic online resource where you can upload your images of different manta bellies & the information will be added to the database to help track the different individuals.

So far there have been over 12,500 individuals identified using Manta Matcher.

Here in Komodo we have our own adopted manta called Gizmo! Gizmo is melanistic (or ninja!!) and was first identified in August 2011. Gizmo has been regularly seen over the years cruising around Mawan and Karang Makassar in Komodo. She is not thought to travel much further than Komodo and seems to be a like spending her time around here! The last time Gizmo was formally identified was in 2023 so perhaps you can help us find her again this year!!

Over at Scuba Junkie Penida they also have adopted an individual called – Mola The Manta. Mola the Manta, like Gizmo, is also melanistic and was first identified in March 2014.

These melanistic beauties are still Manta Alfredi or Reef Mantas. The Melanism is a genetic colour morph that results in a “switch” of colours. Melanistics are commonly referred to as Ninjas and are a really special sight to see!! The darkness of the black is like nothing you will see! Ninjas make up about 10% of the populations in Komodo and Penida so make sure to keep your eyes peeled next time you visit us.

Mantas can be seen in Komodo all year around with them being seen in bigger numbers at dive sites such as Karang Makassar (Manta Point – not to be confused with the dive site at Nusa Penida), Mawan and Manta Alley. If you really want to increase your chances of seeing these magnificent giants in big numbers the best time to visit is September – October & January – April. These are the months when the seasons are changing and they can often be seen feeding, cleaning and mating around the central dive sites! They can still be seen throughout the rest of the year, but usually in smaller numbers.

If you would like to find out more about the best time to visit us if you are looking for your megafauna fix then please get in touch here.

A common question we hear from divers and snorkelers is ‘Is it safe to dive with sharks?’ In short, yes, it is 100% safe to dive with sharks in the Komodo National Park. In fact, in the majority of places in the world it is safer to dive with sharks than it is to try and get chocolate out of a vending machine! So let’s have a little look at why people are so worried about diving with sharks and the actual facts about diving with these amazing animals.

Films & the media

The film Jaws has a lot to answer for, the famous soundtrack springing to mind as people head out to open water. Even as a seasoned dive instructor myself I can’t help but hear that music sometimes when surface swimming back to the dive boat! After the release of the film in 1975 the populations of large sharks plummeted across the globe as people hunted them to ‘protect’ people, most notably in Australia and the east coast of America. Scientists scrambled to explain the importance of sharks to our ecosystem, but the fear that had been instilled from the film was the overriding emotion.

Sadly it seems Hollywood didn’t learn their lesson and still there are films being made that portray sharks as vicious hunters of humans – such as ‘The Shallow’ (2016) and ‘The Meg’ (2018).

With such films being made it is easy to see why people have concerns about getting in the water with sharks; even if someone understands they are important to the ecosystem it doesn’t mean they won’t be scared of them. So let’s look at some facts about sharks and whether or not they pose a threat to us humans.

Can all sharks actually attack us?

There are over 500 species of shark and of that 97% of them are physically unable to hurt humans – either because their mouth isn’t big enough to bite us or they are simply too small to do us any harm (the smallest species of shark, the dwarf lantern shark, reaches just 9 inches!). So already you should be feeling less worried as of all the sharks in the ocean there are very very few with the ability to hurt us!

And those with the ability to do so, do they actually want to? In the movies sharks are portrayed as actively hunting and eating humans, but with the shark attacks that do happen this is simply not the case. Sharks do not want to eat humans, we are not part of their diet and not something they find tasty. Do you think a scuba tank and all that equipment looks appetising to a shark? When they could be saving their dinner for a nice tasty grouper?!

Shark attacks happen due to mistaken identity. Do you know what great white sharks do love to eat? Seals! Seals are a delicious dinner for them. Do you know what a surfer looks like from below?

It would seem that shark attacks are a case of mistaken identity and as soon as the shark bites a human and realises they are not a tasty seal or grouper, they are no longer interested. Sadly, of course, this does lead to fatalities and we are not diminishing that. However, many survivors of shark attacks go on to become fierce advocates for this misunderstood fish.

What species of sharks can attack humans?

There are three species of shark that are responsible for the majority of shark attacks

(None of which are seen in Komodo, by the way!)

These sharks should be treated with respect, in the same way you wouldn’t go and pet a hungry lion or tiger. However, that doesn’t mean we should stop ourselves from enjoying the ocean just because they are there.

How likely is it to happen?

Every year millions and millions of people explore the ocean – swimming, diving, snorkeling, surfing – yet in 2020 there were just 57 unprovoked shark attacks worldwide, 10 of which were fatal. This is the lowest recorded number since 2008! And you know what? None of those happened in the Komodo National Park, or the waters surrounding this area.

Not that we want to scare you, but here are some things more likely to cause a fatality than a shark:

However, you don’t see the media creating horror films about man-eating vending machines! Sadly, the visuals of a shark lends itself very easily to that of a man-eating killer. In actual fact, the majority of shark species are shy creatures who are just trying to survive in a world where mankind is out to get them.

Why should I care about sharks?

Every year over 100 million sharks are killed and this is devastating for our beloved oceans!

To explain this briefly:

Sharks are an apex predator, meaning they help to control the marine life populations below them in the food chain. Without sharks oceans are seeing an increase in larger predatory fish species such as groupers who feed on herbivores. This means there are less herbivores in the ocean, which leads to an increase in ocean plants that suffocate corals. Corals die out and so reef fish are left without homes, meaning they also die out. Not only does that mean no fish (an important food source for millions and millions of people across the world), but also corals are responsible for about half of the world’s oxygen (which they produce through photosynthesis – we’ll have another blog about this later!)

Basically: healthy shark populations = healthy ocean ecosystems = a healthy world

So, ready to come and see some sharks?!

We have had hundreds of divers and snorkelers explore the ocean with us here in Komodo every year, many of whom had never seen a shark before. After getting past their initial fears, they loved getting in the water with the graceful and beautiful creatures.

Swimming with reef sharks is completely safe! Don’t just take our word for it, sharks can be seen at all Scuba Junkie locations (Mabul / Sipadan, Nusa Penida and Sangalaki) and all our crew and guests love them there as well!

We see sharks on a daily basis when out in the Komodo National Park, check out our dive and snorkel packages and come and join us in swimming with these beautiful creatures! Or send us an email for more information

It is often the case that the Manta Rays get all the attention, and whilst we love them and their graceful ways, there are many other marine species that are equally as fascinating to look at and that we see regularly in the Komodo National Park.

Take for example…THE TURTLE!! Known by many as the chilled out surfer type from Finding Nemo, these guys were perfectly cast in the role. What else do we know about this amazing marine creature?

All species of turtles are endangered or critically endangered – you can check out the IUCN red list for more information about this.

We are lucky enough to see three species of turtle in the Komodo National Park – Green Turtles, Hawksbill Turtles and Loggerhead turtles. With the area being protected we hope that numbers of turtles in the area, and across the globe, will start to increase.

Thank you to google for some of the photos!